Ethnicity, Race, and Nation

Roadmap

What We’ll Cover Today

How to conceptualize ethnic phenomena in comparative perspective.

- Are there meaningful differences between ethnicity, race and nation?

- Yes and no!

- Are there meaningful differences between ethnicity, race and nation?

How can we measure “ethnicity” at different levels of analytic abstraction?

A closer look at some of my own work on popular nationalism—that is, the nationalism ingrained within individuals.

- How legacies of geopolitical trauma shape popular nationalism today.

- How attitudes about the nation can carry distinct meanings—and map onto disparate claims—along the majority-minority divide.

Conceptualizing Ethnicity

What is Ethnicity?

“We shall call ‘ethnic groups’ those human groups that entertain a subjective belief in their common descent because of similarities of physical type or of customs or both, or because of memories of colonization and migration” (Weber 1968).

- My view: race and nationhood can be understood as subtypes of ethnicity (cf. Wimmer 2008).

How can we reconcile this definition with the one outlined in your textbook?

- Race, ethnicity and nation can carry different meanings—but these are often context-specific and rarely align with folk distinctions (see Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004; Loveman 1999).

- For an alternate perspective, see Winant (2015).

A Social Construction

All forms of ethnicity are socially constructed—the product of political entrepreneurship, cultural contestation, social movements, mythcraft and the ghosts of history.

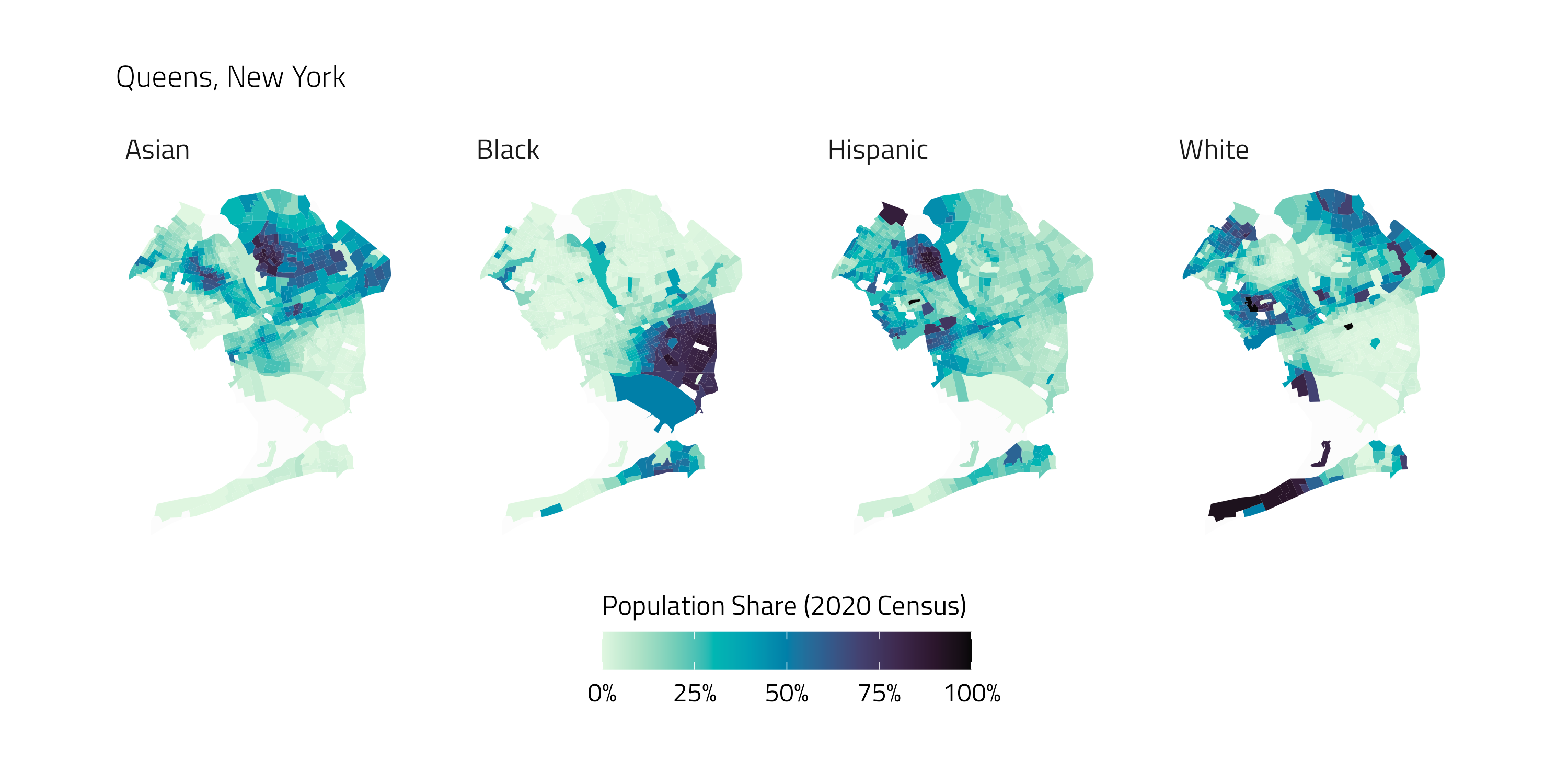

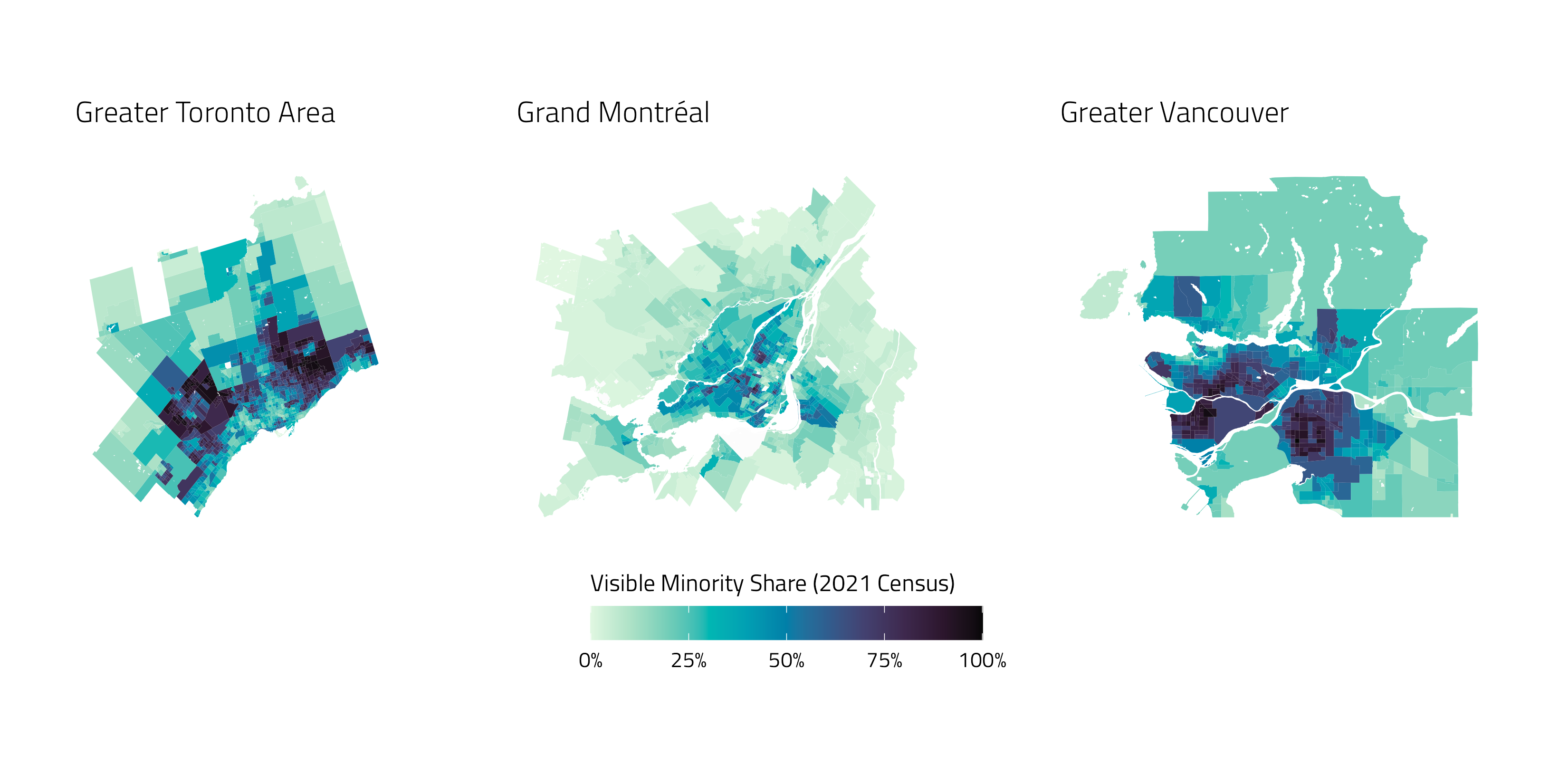

Even as a “construct,” the material and psychosocial consequences of ethnicity can be profound. For example, consider the durable patterns of ethnoracial segregation that define modern cities.

A Social Construction (cont.)

Groupism and Groupness

In studies of ethnicity, race, and nation, groupism routinely rears its head.

- A tendency to position “internally homogeneous and externally bounded groups as basic constituents of social life” (Brubaker 2004).

When analyzing social groups, analysts should shift their focus to groupness—e.g., conjunctures defined by ethnic solidarity and cohesion as opposed to fragmentation or detachment.

A focus on groupness can help scholars identify when ethnic distinctions become socially resonant and when the boundaries between ethnic units harden or shift (cf. Kuran 1998).

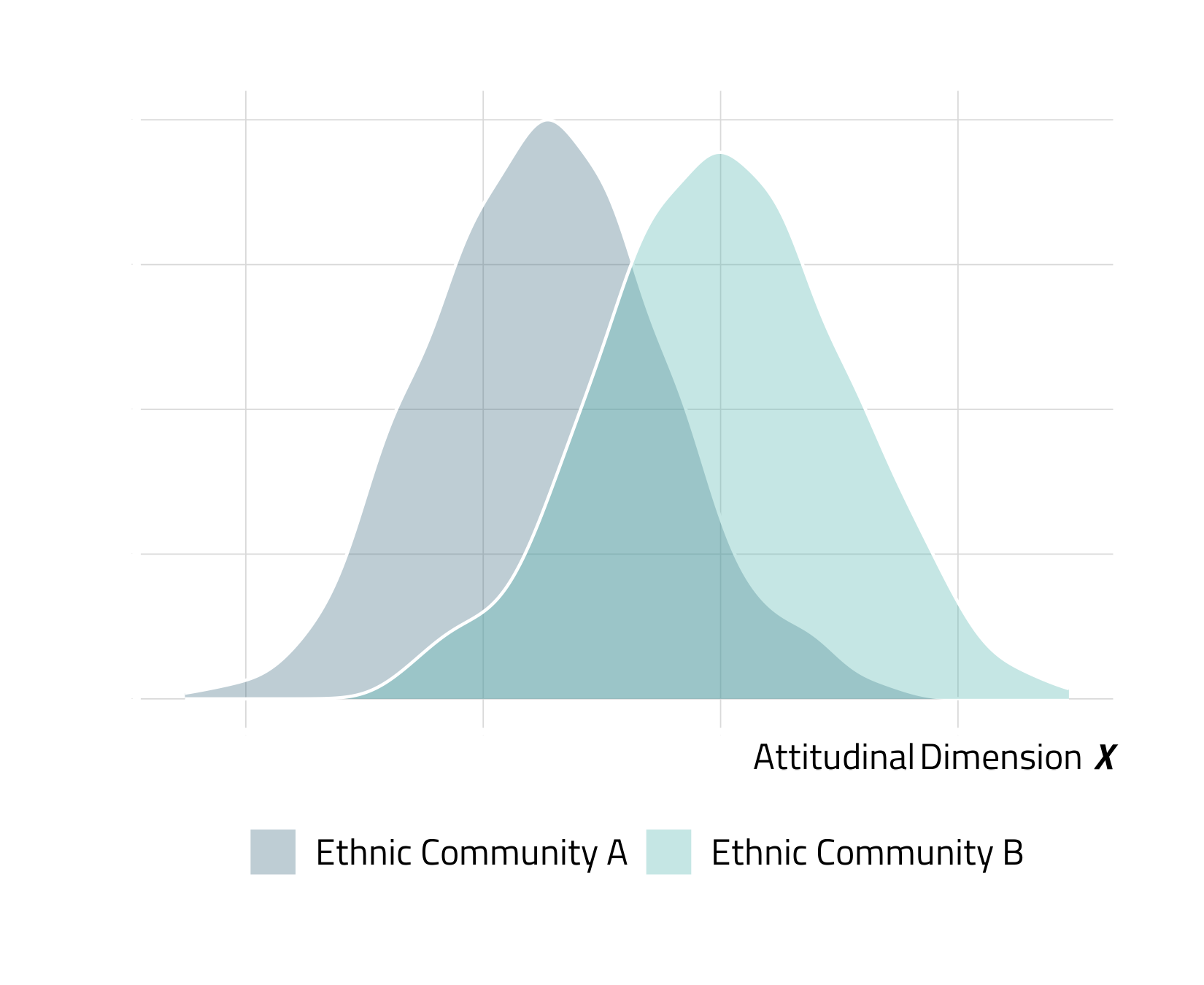

Intragroup Heterogeneity

To avoid groupism, researchers should also study variation within so-called ethnic groups—or differences (material, attitudinal, dispositional etc.) within races, ethnicities, tribes, nations, religions and so on.

Pathbreaking studies from a variety of literatures have advanced similar arguments about the importance of highlighting intragroup differences.

- Intersectionality (Crenshaw 1989)

- Boundary-Making (Wimmer 2008)

- Infracategorical Inequality (Monk 2022)

Ethnicity as Cognition

Ethnicity, race and nation should be understood as perspectives on the world, not entities in the world (Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004).

- Attention should be paid to the beliefs, categorization processes, cultural schemas, stereotypes, identifications (etc.) that are anchored to widely-shared ideas about common descent or destiny binding members of so-called ethnic groups together.

How can we think about “ethnicity as cognition” in concrete terms?

- Find nation-state schemas in social survey data (e.g., Bonikowski and DiMaggio 2016).

- Study colourism to understand how cues of categorical membership structure inequality (see Monk 2022).

- Treat immigrant identifications as nodes in belief systems (some of my ongoing work!).

Measuring Ethnicity—

Some Quick Examples

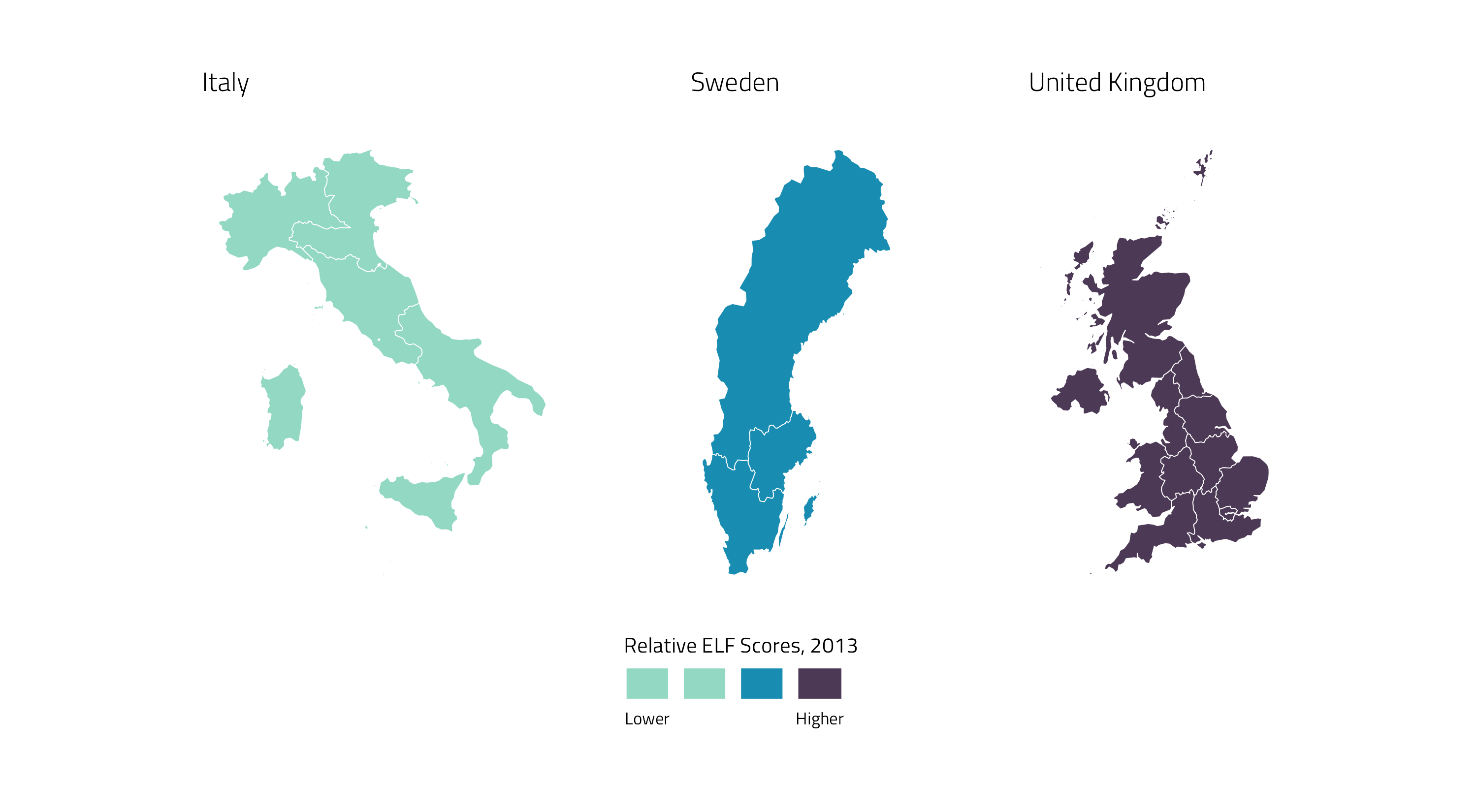

Ethnic Fractionalization Index

Image generated using data from the Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalisation Dataset.

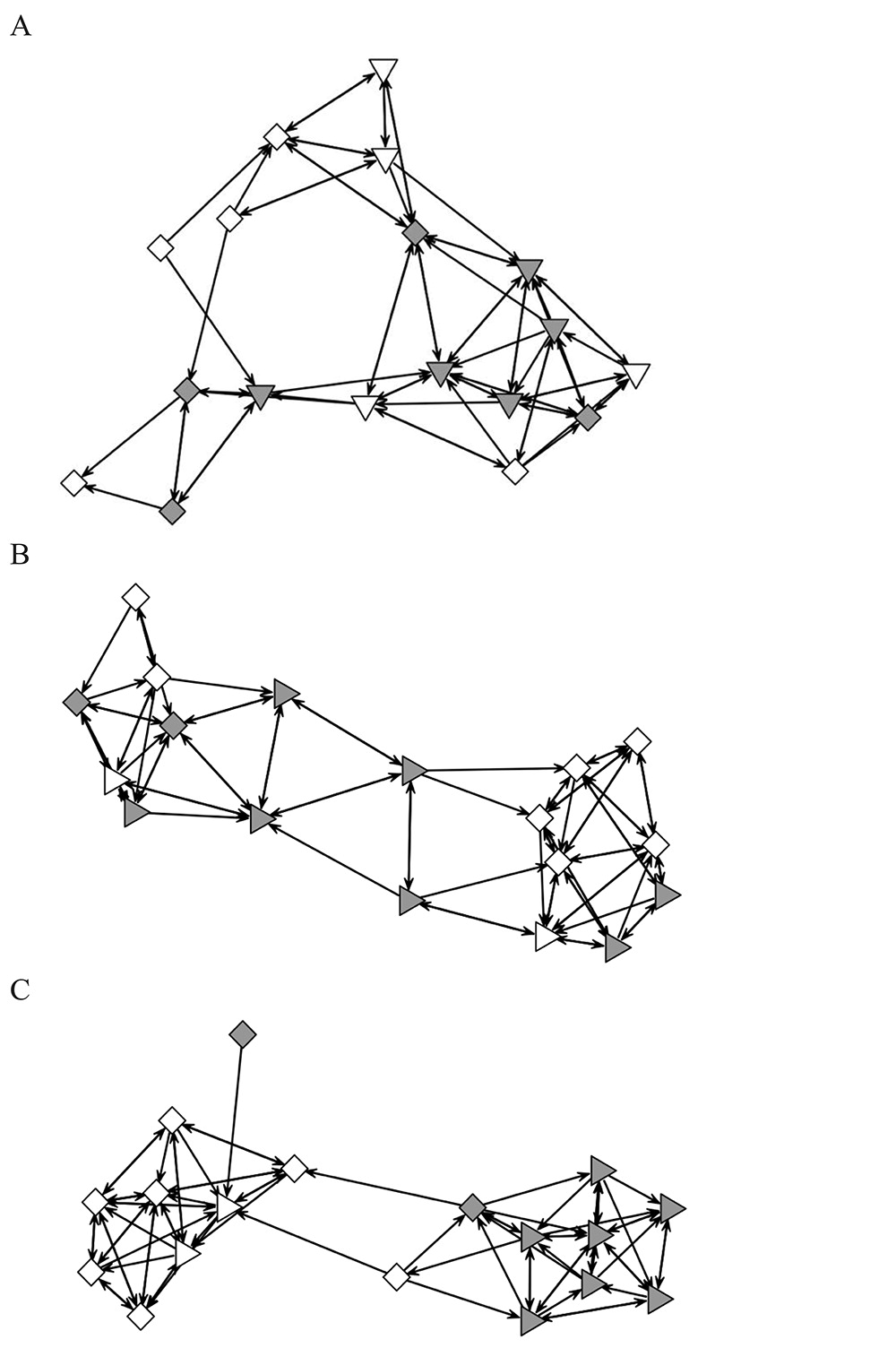

Racial Classification via Conjoint Experiments

Experimental manipulation can help us understand how individuals racially classify others—and construct ethnic boundaries in the process.

Figure 1 from Schachter, Flores, and Maghbouleh (2021).Network Models and Intersectionality

Consolidation can serve as a measure of structural intersectionality.

Image above is Figure 5 from Zhao (2023).

Ethnic Attachments as Belief Systems

We can think about ethnocultural attachments (to our faith communities, origin societies etc.) as nodes in broader belief systems about the self.

Image above is from some of my own ongoing work.

A Closer Look—

Schemas of the Nation

The Nationalist Doctrine

Historically, nationalism was anchored to transformative claims—i.e., to redraw the world map and reimagine the boundaries of geopolitical space (cf. Brubaker 2020).

- Today, it is increasingly anchored to restorative appeals to revitalize the nationnness of the state (ibid).

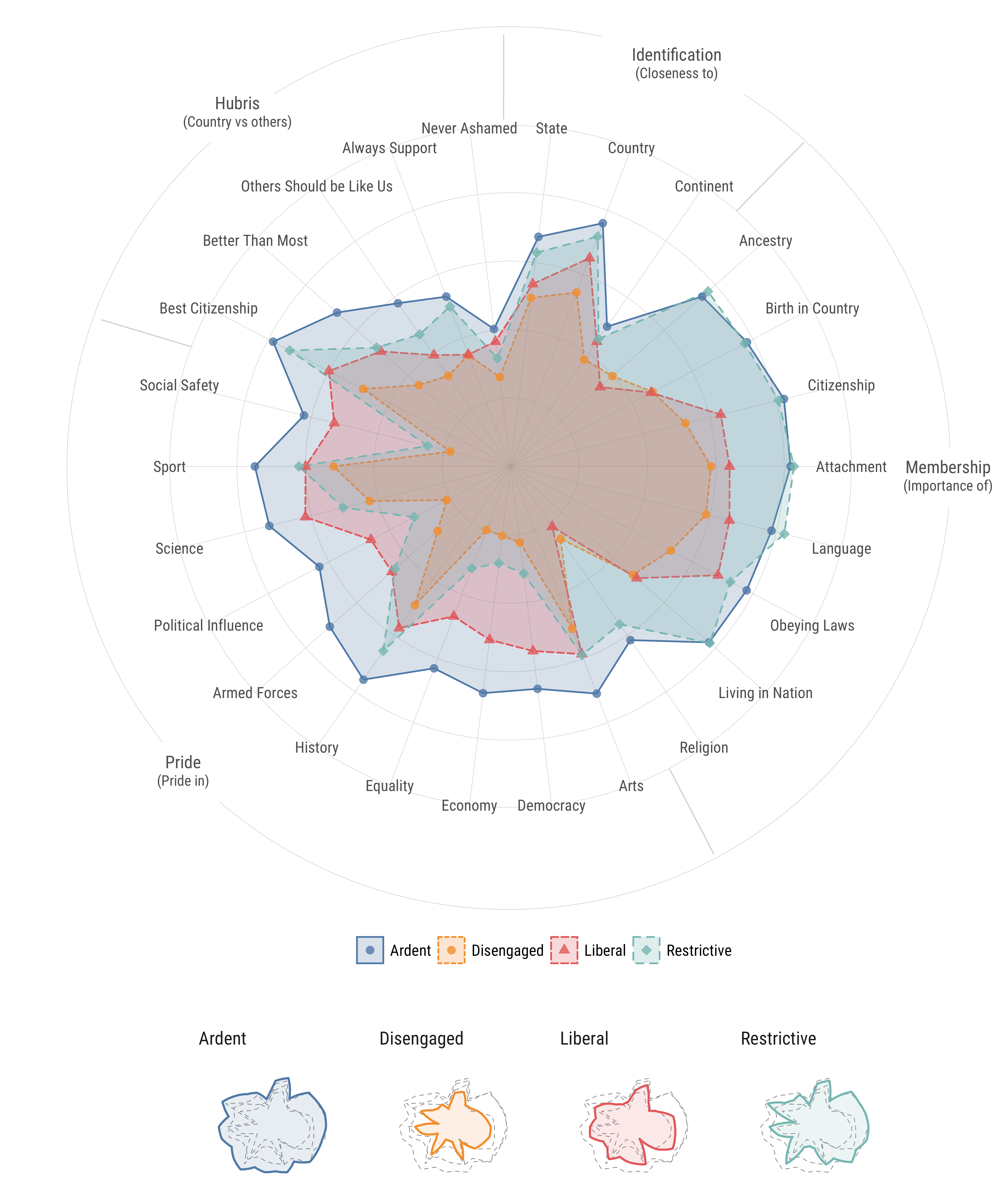

Yet, contemporary nationalism is not solely “restorative” in nature (Bonikowski and DiMaggio 2016).

- Work on popular nationalism sheds light on the varieties of nationalist beliefs—or nation-state schemas—that have emerged in democracies around the world.

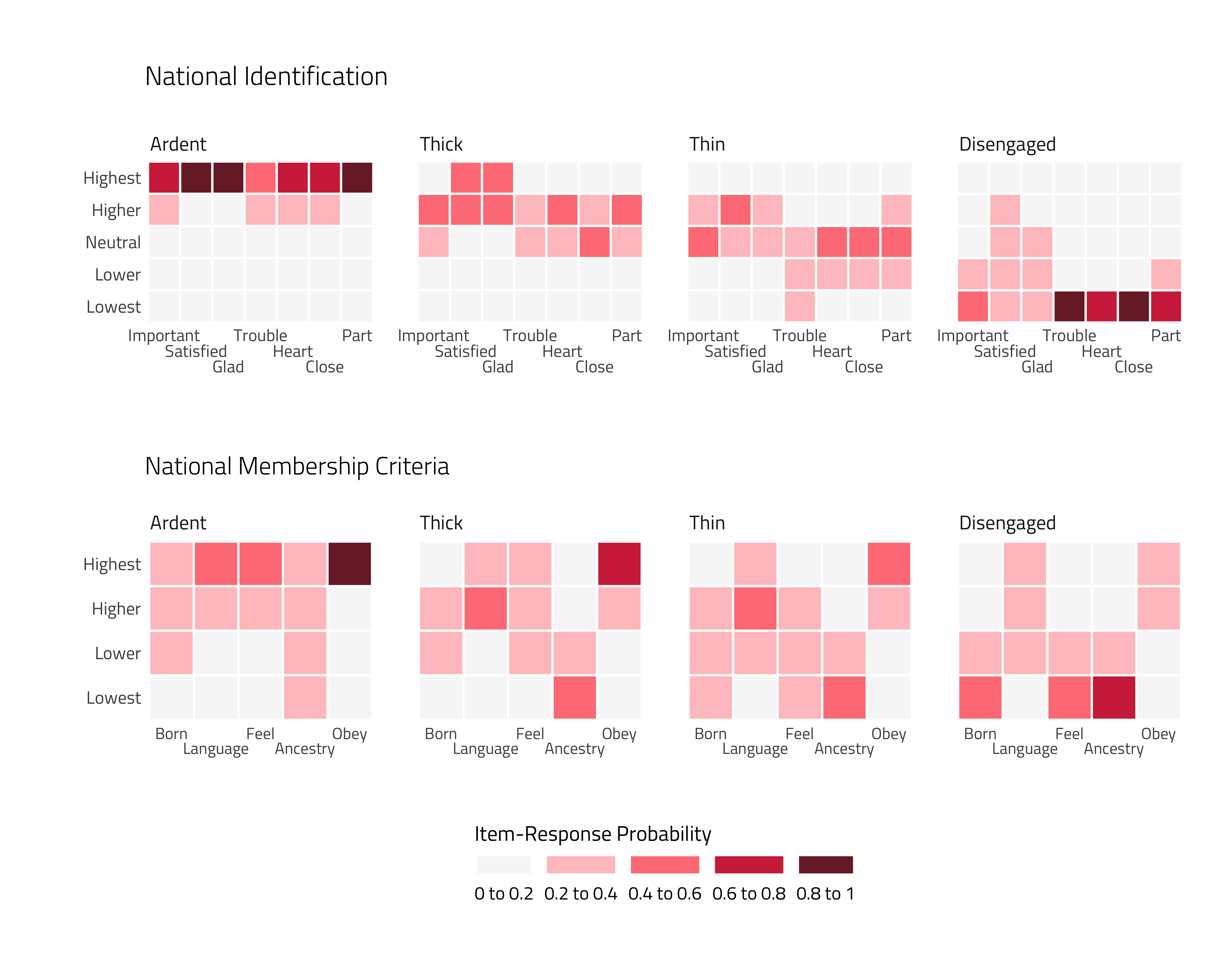

Nation-State Schemas

Image above is Figure 1 from Soehl and Karim (2021).

Nation-State Schemas (cont.)

| Schema | Profile | Identification | Membership Criteria (Exclusionism) | Pride | Hubris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardent | High | High | High | High | |

| Disengaged | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Liberal | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High | Moderate | |

| Restrictive | Moderate | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High |

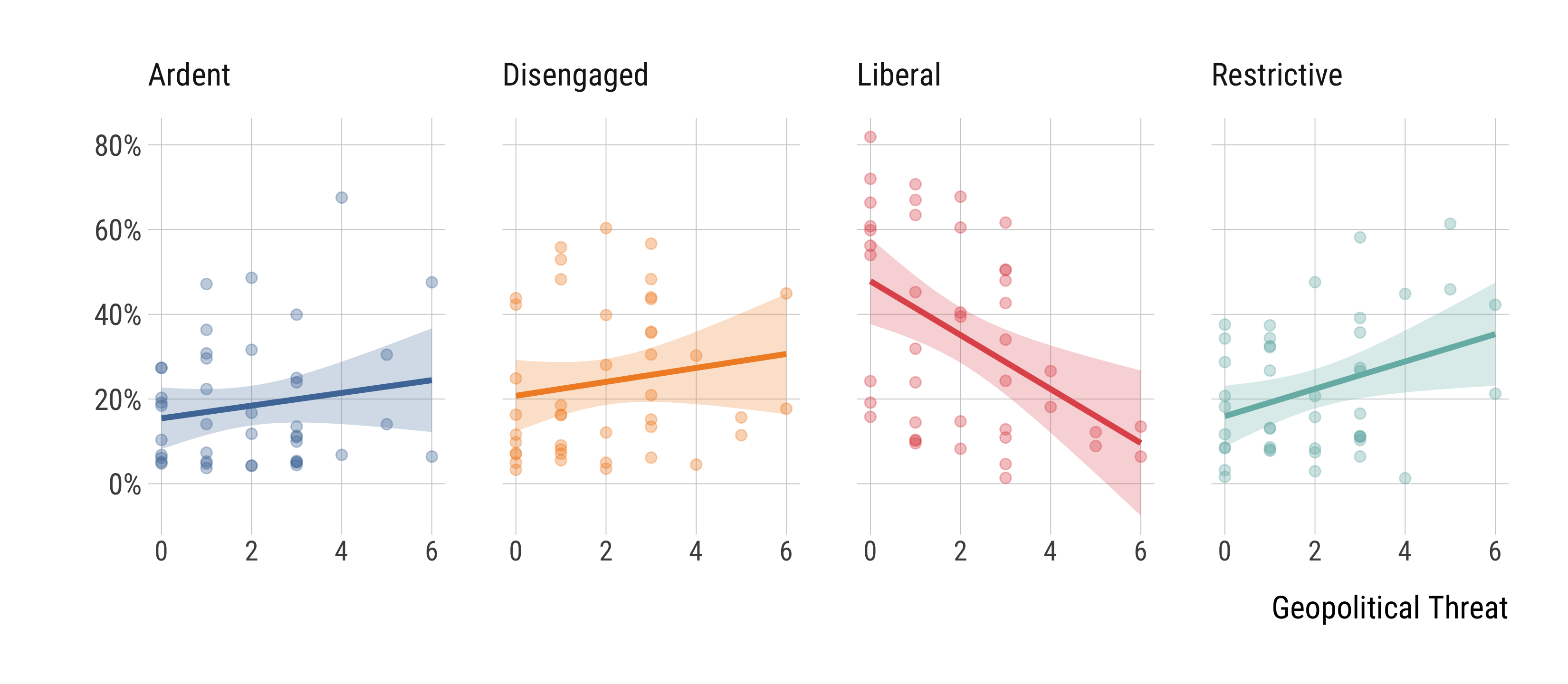

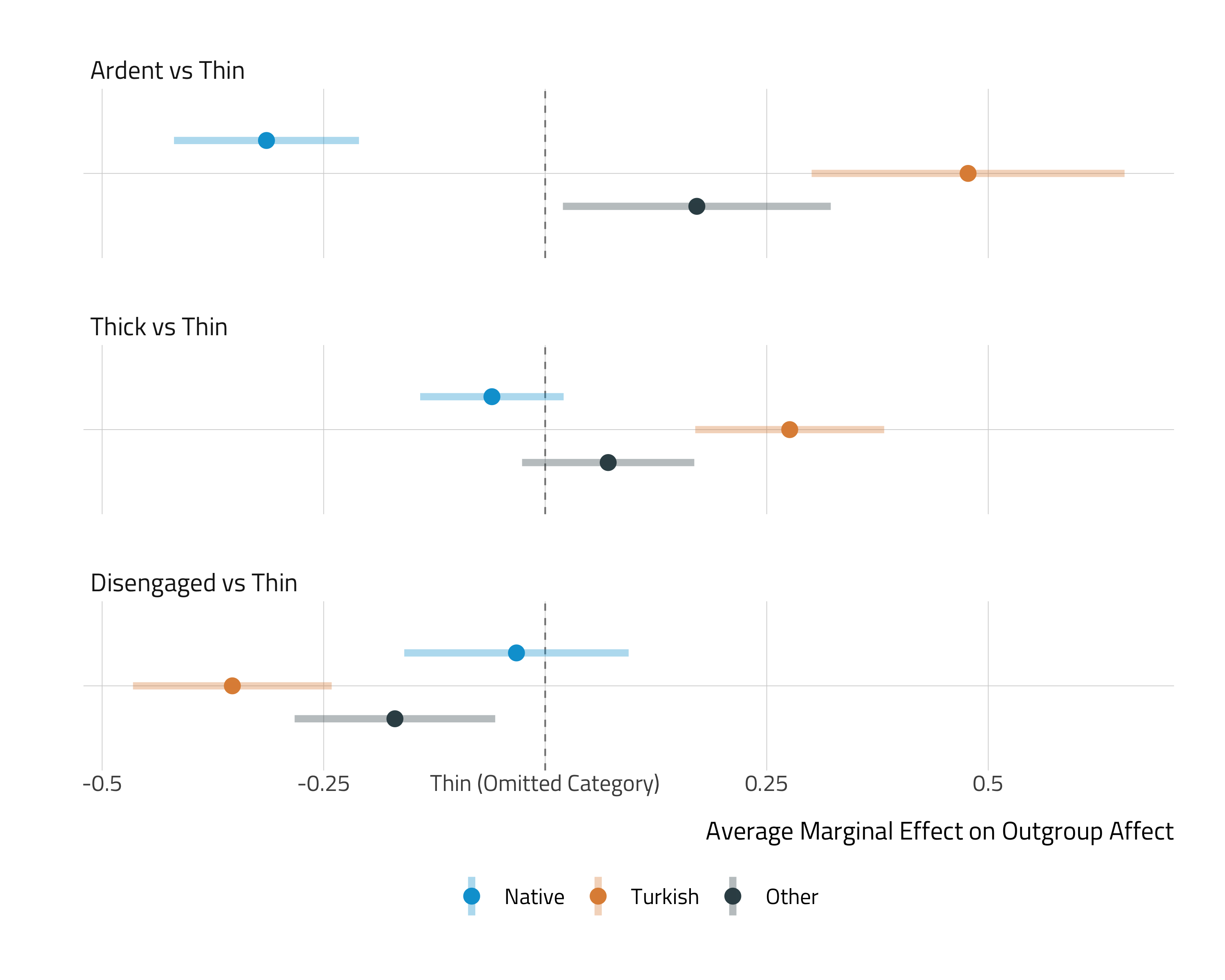

Geopolitical Trauma and Popular Nationalism

Image above is Figure 2 from Soehl and Karim (2021).

Nation-State Schemas and “Ethnicity”

Image above is from some of my own ongoing work.

Nation-State Schemas and “Ethnicity” (cont.)

Image above is from some of my own ongoing work.

The End

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography.